Dyes and Textiles that Communicate Ryukyuan Aesthetic Sense

Ms. Ichiko Yonamine has worked as a curator at the Okinawa Prefectural Museum & Art Museum for many years and has organized many exhibitions of Okinawan dyes and textiles. She says that even from a global perspective, it is rare that there are so many variations to these crafts in such a limited geographical area. We sat down and interviewed her about many things including the charm of cloth from Okinawa, dubbed the “Dye and Textile Kingdom,” the connoisseur’s ways to enjoy crafts in general, and advice to travelers. Join us in the journey to follow craftwork under the keyword, “The Aesthetic Sense of the Ryukyuan People.”

――It’s extraordinary that there are so many variations of dyed textiles in this tiny island country, Ryukyu.

Yonamine: Just on Okinawa Island itself, there are various types of dyed textiles including the bashofu (banana fiber) textile, Yuntanza hanaui (hana-ori (float weaving) in Japanese and hanaui in the Okinawan language) and Chibana hana-ori. There are also the Ryukyu kasuri (made with cotton and hemp threads in the past, but silk is now being used) produced in Haebaru (a town in the Shimajiri District of Okinawa Main Island) and the Shuri-ori (produced mainly in the Shuri area in Naha City), while on the remote islands there are Kumejima-tsumugi, Miyako-jofu, Yaeyama-jofu, and the thick Minsa-ori for obi (sashes). Yonaguni Island also has a form of float weaving. Even on a global scale, it’s rare to be able to travel through production sites with such a rich and wide variety in such a short amount of time.

――Visiting these sites feels like it would be a journey that will give you a whiff of Ryukyuan culture.

Yonamine: Nowadays there are production sites throughout the prefecture. You can learn about the production process and observe actual weaving at places like the Bashofu Hall in Ogimi Village and Yuimaru-kan on Kumejima. Some of these places also have programs where you can actually experience parts of the production process. I encourage you to give them a try!

――That sounds like fun!

Yonamine: Most of these places also sell small items made with the actual textiles. We would love you to use them on>a daily basis to feel how wonderful Okinawan textiles are. At the Fureai Taiken (Touch-and-Experience) Room in the Okinawa Prefectural Museum & Art Museum, you can try on a real kimono (traditional dress). Entering the room is free. There are also swatches of the textiles from all over the prefecture. We would love you to come to take a look at them. In a permanent exhibit, there are lacquerware and ceramics from the Ryukyu Kingdom era to modern times. It’s certainly a place that would delight you if you like crafts.

In the collection of Naha City Museum of History

――Okinawa has many crafts that have a unique style of their own. When you include the performing arts like Ryukyuan Dance, you really see that Ryukyu was a country that regarded “beauty” as important.

Yonamine: Speaking of “beauty,” when you look at the patterns on the clothing and lacquerware, the ones from Ryukyu Kingdom era are often asymmetrical. In fact, the same can be said about Sanshin (traditional three-stringed instrument) and ceramics. The gifts given to the Chinese emperor and shogun of the Edo shogunate are thought to have been excellent items that utilized the most sophisticated techniques of the time. Looking at those, it’s unlikely that they were technically incapable of making symmetric designs. Yet, many of the clothes left from the royal family show slight misalignments of the patterns in the backs and the sleeves.

――So, you are saying that they were technically capable of aligning them, but they purposely didn’t?

Yonamine: My hypothesis is that they felt like symmetrical things felt too constrained. I’m thinking that the Ryukyuan sense of aesthetics was to have a little looseness in the things they used.

――So, not “Yuru-kawa” (short for “loose (yurui) and cute (kawaii)”), but “Yuru-bi” (“loose” and “beautiful”) (laugh)? That’s innovative!

Yonamine: If you look at the artwork, architecture, dyes, and textiles with that in mind, your enjoyment will deepen too.

Bingata-zome

“The vibrant colors that shine in Okinawa’s bright sun leave a strong impression. It is a color sensibility unique to a subtropical zone.” There are two types of dyeing, the one where pigments and dyes are used with stencils is called katazome (form-dyeing) and the kind that is drawn free-hand is called tsutsuzome (tube-dyeing). During the Ryukyu Kingdom era, only people of a certain class were able to wear these.

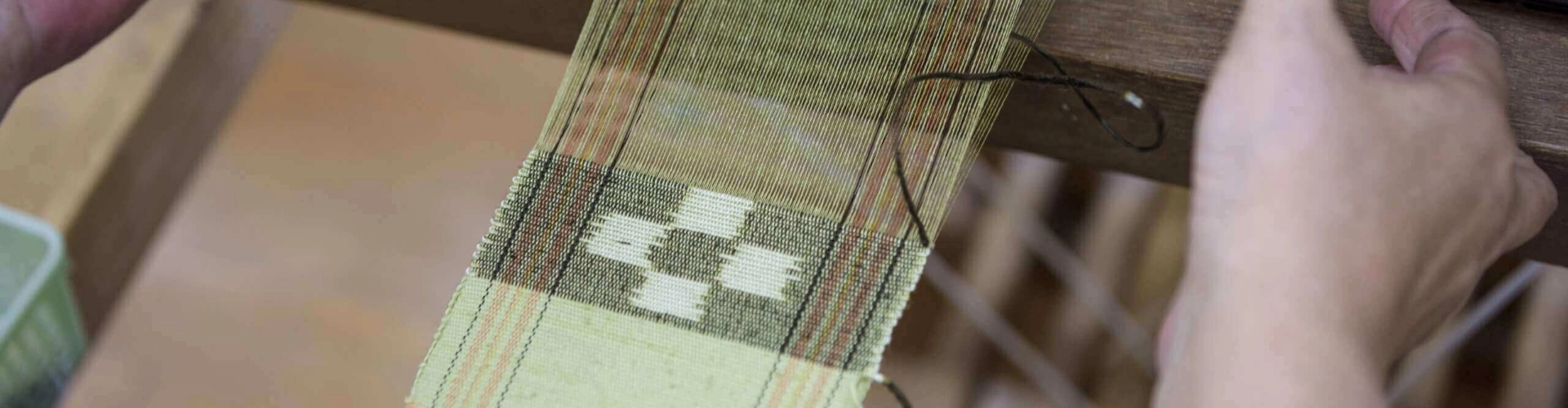

Bashofu

These are weaved from threads made from the trunks (more accurately, stalks) of a type of banana tree known as itobasho. “Now it’s considered as a luxury item, but up until a couple of decades ago, every household had some bashofu ‘belonging to grandma’ tucked away somewhere. It is possible to get the delicate thread from the middle of the stalk and rougher thread from the exterior part, so during the kingdom period, all kinds of bashofu were made, ranging from the thin delicate silk-like fabric for the ruling class to the rough fabric for work clothes for commoners and boat sails.”

Kumejima-tsumugi

Kumejima-tsumugi is a splash-patterned fabric weaved with silk threads that are dyed with natural ingredients such as Ryukyuan doro-ai (“mud” indigo) and plants. The classic color combination is deep black and a color ranging from brown to yellow. There are also “natsu (summer) Kumejima,” which are thin and light.

Miyako-jofu

This is a fabric dyed almost black and very deep indigo made by weaving a thread called vu made from Ramie that is dyed with indigo several times. Since the thread started being tightened by machinery in modern times, it has become possible to express a complex pattern of small cross-shaped patterns. Another unique point is that the whole cloth is given luster and a firm texture.

Yaeyama-jofu

Linen specialized in the kasuri-pattern of plant-based dyes on a white background, made with Ramie thread. To make the pattern bright, the fabric is exposed to strong sunlight or seeped in ocean water. “In terms of both the ingredients for the dyes and style of exposure, it strongly evokes a lifestyle that was integrated with nature.”

Yachimun

Yachimun means pottery in the Okinawan language. While what is often valued is the quick brush stroke on the heavy-set earthenware and its southern laid-back feel, the ancient ceramics from the Ryukyu Kingdom period had more intricate designs. “One of the ways to enjoy them is to compare them in museums and art museums.”

Lacquerware

The most noticeable part of Ryukyuan lacquerware is the original three-dimensional decorative technique called tsuikin, which was born of the high-temperature and high-humidity climate of Ryukyu. During the Ryukyu Kingdom period, the artisans serving the royal government crafted these as diplomatic gifts. The incredibly detailed and sophisticated technique such as “gold-inlay” (a technique where the gold foil and gold powder is pushed into the lacquer engravings) and “mother-of-pearl inlay” (a technique that inlays the thinly sliced pearl layer inside a limpet on a lacquer surface) are still passed on to the present day.

Goldsmithing

Jifa, the uniquely shaped hair-ornament for men and women, and fusa yubiwa (tassel rings), the clustered rings with seven auspicious symbols that warrior-class parents gave to their daughters when being married off wishing for their happiness, are still created in individual goldsmith’s workshops. “Even the King’s hair ornament is partly asymmetrical, and you can see the unique Ryukyuan aesthetic sense there.”